Introduction

As a non-disabled person myself, I’d only ever considered how social media impacts the world through my non-disabled lens: Social media is fun, it’s silly, it’s frivolous and often vacuous, it’s becoming a chore, etc., etc. It had never occurred to me that, for some communities, social media is not just a nuisance that’s sometimes fun—for better or worse, it’s their world.

Social Media Accessibility Series

Part 1: How Does Each Platform Measure Up?

Part 2: How to Make Your Social Media Content Accessible

Part 3: How to Make Your Social Media Videos Accessible (Step-by-Step Guide)

Part 4: Is Social Media Accessible? Three Disabled Users Share Their Experiences

Part 5: Video Accessibility on YouTube and Vimeo

“There’s no community for people like me who can’t drive, who can’t go anywhere. We rely on social media to find people. It can be your whole world because you’re disabled.”

Those words, spoken through tears, stopped me in my tracks. Heather S. Neff, founder of accessible graphics company Equivalent Design was talking about what it’s like to navigate the world with motor and vision impairments.

As a non-disabled person myself, I’d only ever considered how social media impacts the world through my non-disabled lens: Social media is fun, it’s silly, it’s frivolous and often vacuous, it’s becoming a chore, etc., etc. It had never occurred to me that, for some communities, social media is not just a nuisance that’s sometimes fun—for better or worse, it’s their world.

But what most caught my attention about Heather’s words was that she said them while explaining how, despite being reliant on social media to market her business and to have any semblance of community with people who understand what she’s going through, those very platforms are literally causing her pain every day because of their lack of accessibility measures.

Disability Exclusion Is Still a Reality in 2022

That may sound extreme, but it’s not. Millions of people like Heather who have visual, auditory, and information processing impairments are often excluded in one way or another from our digital world, despite being the very people who rely on it the most.

A visual impairment often means not being able to see images, words, or art, as well as experiencing pain from light and movement. An auditory impairment means relying on captions to know what’s being portrayed in videos. An information processing impairment means that cool graphics, buttons, fonts, and other ways we communicate information can be difficult to understand.

That’s why web accessibility is paramount. Accessibility requirements exist to make sure that all people can understand and experience content on the web. But the non-disabled world has been slow—reluctant, even—to meet these requirements, citing a variety of reasons like the cost, not having enough time or resources, or that it’s just too hard.

But we think the biggest reason is that many of us have never had to experience the internet the way disabled folks do. If we had, we’d understand why all of the aforementioned barriers must be overcome.

So, to try to bridge the gap between the disabled and non-disabled experiences, we invite you to read the stories of three women and discover what it’s actually like to navigate social media as a disabled person in 2022.

Lily Mordaunt

“I think it's very easy for people to underestimate how much social media influences our daily lives—the memes we laugh at or the TikToks we imitate—unless they are the ones being left out.”

Currently a creative writing student at the Queen Mary University of London, Lily is a voiceover artist and an aspiring editor. She is also blind and uses screen reading software, like Apple’s Voiceover, to navigate social media on her phone, as the layouts on both desktop and tablets can be less familiar and require more maneuvering.

Despite using Instagram the most, she likes it the least because very few people add alt text to their images or audio description to their videos. Between that and a less-than-helpful caption, she said, it’s pretty useless: “I post my life and can’t interact much with the lives of others.”

It may come as no surprise, then, that when we asked her what her primary emotion is when using social media, she said, “I mostly feel resigned that I just won’t have all of the information.” Despite a desire to connect and be included, she is prevented from doing so because, for her, the information is just out of reach.

Lately, she’s found herself gravitating away from the bigger platforms like Twitter and Instagram and toward predominantly text-based platforms like Reddit. This is partially because of accessibility, but also because Reddit makes it easier to customize the content in her feeds. Since COVID, she feels that Twitter (her go-to platform previously) has been full of sadness and negativity.

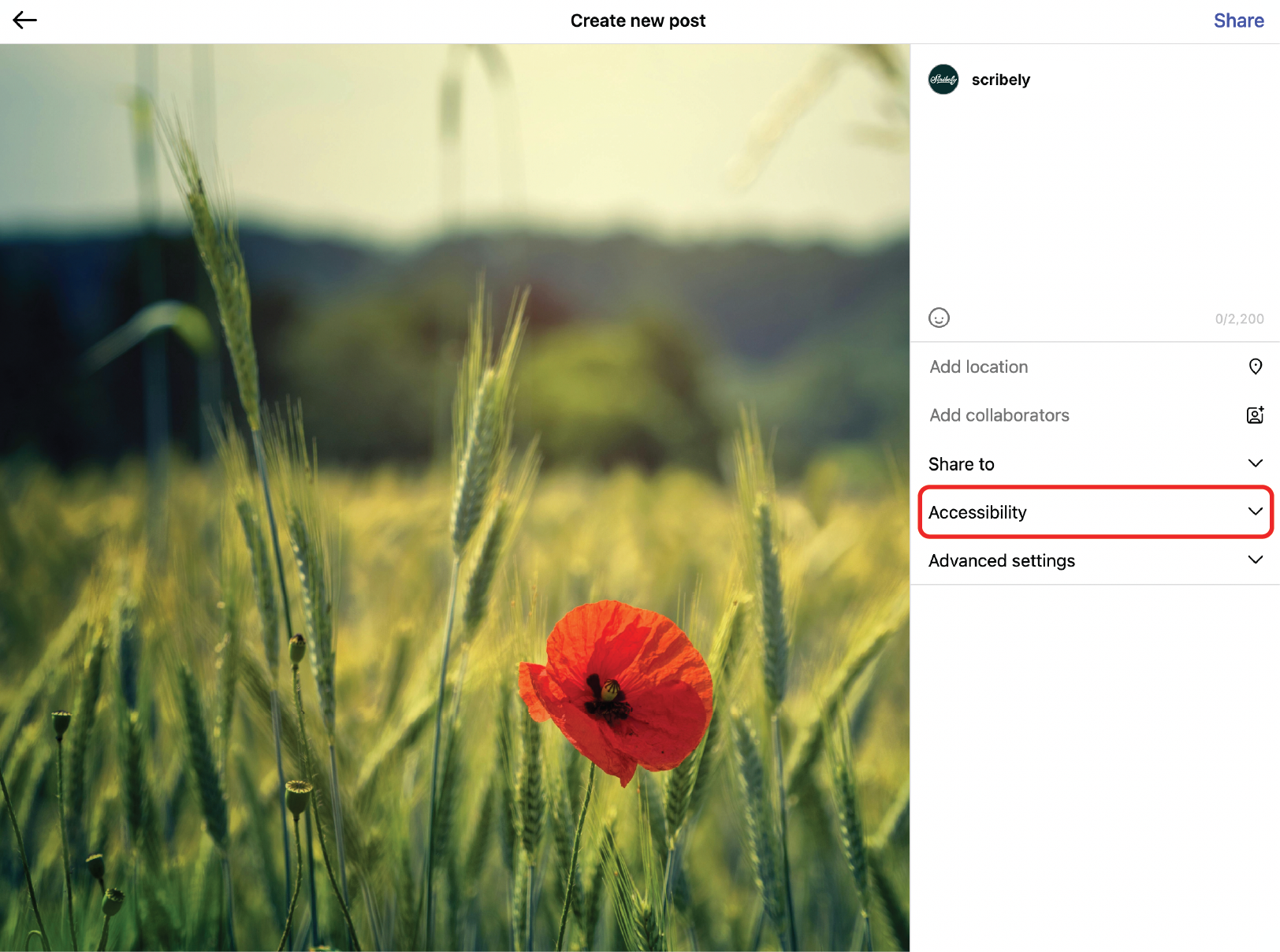

Ultimately, she hopes that both platforms and their users will take steps toward ensuring that information is put within everyone’s grasp. For platforms, she asks that they don’t hide alt text in advanced settings, but instead “make it easy to find so that users don’t feel like it's a chore to make their posts accessible. Also, promote it. So many people have never heard of alt text and that may come down to overall disability awareness, but platforms can definitely contribute to spreading the word.”

For non-disabled people, when posting content she encourages, “Be conscious that there are people with varying abilities viewing your posts, especially for big pages like brands and influencers.”

Noting that all accounts regardless of size should utilize alt text and captions, Lily says it’s really important that influencers use their platforms to promote accessibility because “it can feel even more isolating if, for example, your favorite celebrity is posting images that everyone is commenting on and interacting with and you have no clue what's happening. But also, I personally just want to laugh at the video or try out the new recipe too.”

Meryl K. Evans

“It's okay to ask someone to caption their video or add an image description. Just be kind and be flexible. Some people won't respond. Move on. Some will. Celebrate those victories.”

Meryl is a professional speaker, trainer, consultant, and writer focusing on accessibility and inclusion. She is also deaf and requires captions to know what’s being communicated audibly in videos.

Meryl is no stranger to social media as she uses it to spread awareness about web accessibility and inclusion, as well as to educate others about how to make their content more accessible. Thus she’s pretty familiar with the good, the bad, and the ugly of social media accessibility.

According to Meryl, the ugly of video captioning on various platforms is actually when they try to make it pretty. For example, Instagram and Facebook offer four different caption styles, and none are ideal. She said that of those who add captions to their videos, people tend to choose the first style, “which is actually the worst in terms of accessibility.” It’s all uppercase, white (which means the contrast is often bad on lighter backgrounds), and has different font sizes. All of these are the exact opposite of what’s recommended for captions.

So is there a platform that does a good job with captions? According to Meryl, TikTok “because creators can’t customize the captions.” Instead, they offer one style, which is formatted like the closed captions you see on TV and in films, with white text on a black background in a simple, easy-to-read font.

If there were one thing she’d urge social media users to do, it’d be to add image descriptions and video captions. Not only are image descriptions easy—“Just describe the key points”—they make a difference. And captioning videos will “expand your reach far more,” despite the extra time it takes to ensure they are correct.

And for users who want to go above and beyond, she encourages you to make sure the text in your images is readable: “So much of it is not readable. It’s the simplest thing. Font size, style, color, and contrast with background all matter.” A few of Meryl’s tips for making text more legible:

- Avoid centering text.

- Avoid bolding more than three words.

- Avoid italicizing more than three words.

- Avoid using a variation of gray on white. “It resembles reading in a fog.”

Heather S. Neff

“There are a lot of issues around disabilities that most people don’t understand. So many people don’t recognize the impact accessibility can have for us. We’re trying to keep people alive and give them hope.”

Heather is the founder of Equivalent Design. She also has photophobia (light sensitivity) and other visual and motor impairments. She uses dark mode with the brightness as far down as it will go and voice commands to navigate social media.

Heather is reliant on social media for spreading the word about her company, as well as for educating the masses on the importance of accessibility. So like many of us, she uses it every day for work, but unlike most of us, she suffers physically from doing so: “I am in a lot of pain from social media, to be quite honest.”

Things like graphics on a white background or auto-playing thumbnails hurt her eyes, eventually giving her migraines. Despite this, she still loves Instagram because she’s a designer, and “it’s very appealing for its imagery.” She loves that they now have alt text but warns against becoming reliant on their AI-generated descriptions because the technology isn’t there yet. She believes in 30 years, it will have come a long way, but right now the descriptions it generates are often worse than not having descriptions.

When it comes to making content more accessible, she urges users to format their text-based images for each individual platform and to use nine words or fewer in the images themselves—“Less text is more accessible.” She says that putting the rest of the info in the caption is more accessible for more people.

As a graphic designer herself, she says all this with the full understanding of the frustrations that come with designing for accessibility: “It’s impossible to always design for everyone.” That’s why she believes that a lot of the onus is on the platforms: “User preference needs to be listened to and experiences need to be customizable.”

How, exactly? Heather has many suggestions, from the ability to customize the size of the text, making layouts more responsive and flexible, and filtering out or dimming images. “I want customizations on the microscopic level,” she says, “so that I can make it work for me and allow me to do what I need to do. Use that AI for good. I should be able to filter out whatever I want.”

Her final recommendation applies to both platforms and individual users: “Pay attention to user experience and not just complying with standards.” Because not only is it the right thing to do, also for many disabled people, this is their world we’re talking about.

Conclusion

As you may have noticed, each woman has different needs and pain points when it comes to devices and the internet. But rather than letting that hamper our progress, let it spur us on to recognize that customizability isn’t simply about preference, it’s about real people’s real needs.

Yes, it may take longer to create different sizes of images for different platforms or to edit the auto-captions to accurately reflect what a video says before posting, but when considering how big of a difference those few extra minutes can make, isn’t it worth it?

Huge thanks to Meryl, Heather, and Lily for their willingness to share their experiences and for their honest vulnerability. Please follow each of them to learn more about accessibility and to support their endeavors.

Check out Scribely's 2024 eCommerce Report

Gain valuable insights into the state of accessibility for online shoppers and discover untapped potential for your business.

Read the ReportCite this Post

If you found this guide helpful, feel free to share it with your team or link back to this page to help others understand the importance of website accessibility.

.jpg)

.jpg)

_edited_6x4-p-1080.jpeg)